Digital Transitions, Featured Photographer, Photographer Profile

Featured Photographer – Kevin Saunders

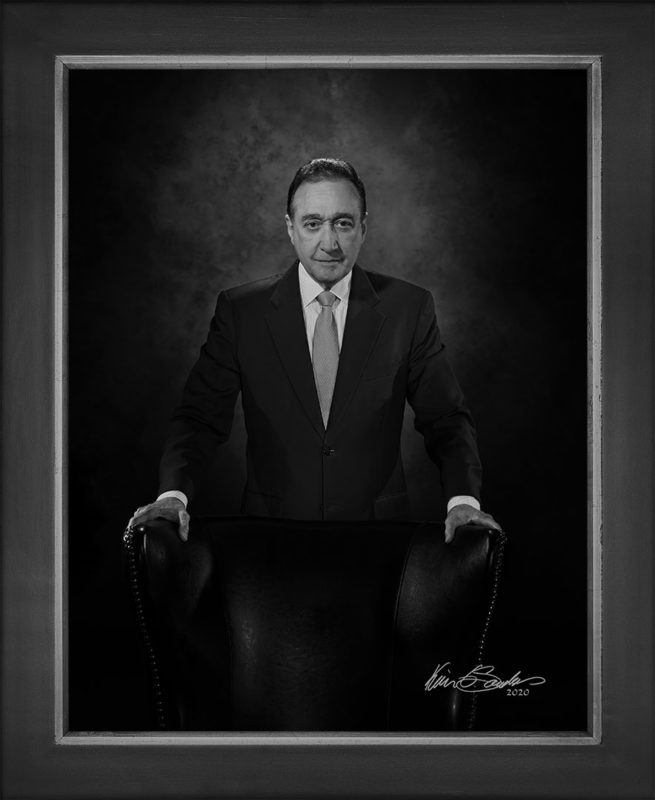

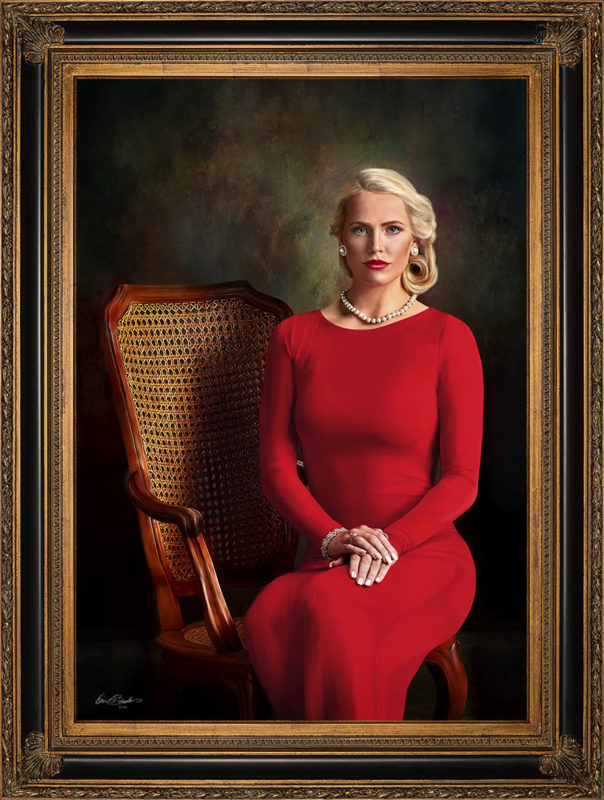

This month, we are proud to feature the work of San Antonio based photographer, Kevin Saunders. Kevin is inspired by the work of master photographer Yousuf Karsh and has been able to mimic his techniques in his own work. Continue reading to learn more about his work and see examples of his dramatic portraiture.

Describe your approach to photography— What makes your work unique?

My approach to photography is truly to paint with light. I have evolved from hyper realism through huge stitched landscapes and cityscapes to carving out a niche in large scale portraiture, thanks to the resolution I get with the IQ4 back and either my Arca Swiss M Monolith view camera or my XF system DSLR. I use a psychological approach to portraiture, to get into the subject’s head and find the dignity and emotion prior to opening the shutter. Therefore I make very few exposures but I know exactly what the image will look like when I do open the shutter.

What inspires you? Who are your influences?

I had the opportunity to really look myself in the mirror when challenged by a long form photojournalist in 2014 who said, “Your work is some of the best in the world but you aren’t putting important enough things in front of the camera.” I was not doing portraiture in any focused manner at the time and I really focused inward while studying all the masters. Yousuf Karsh was my greatest inspiration in black and white. I studied both Karsh and Hurrell and reverse engineered the process with fresnel lights. Over the years I built up a black and white studio that gave repeatable results. I figured out what they did and uncovered many of their secrets. I developed digital negative printing techniques and built a darkroom so I could print on gelatin silver paper. In 2016 I added color to the mix, inspired by John Singer Sargent. I saw a visual voice emerging and have developed it ever since. I now focus exclusively on huge wall portraits and market them to a discerning audience worldwide.

What was your first camera?

My father had a Leica M3 that I used back in the 1960’s. He used to take me out and say, “See that light? What’s the aperture and shutter speed?” I didn’t know it at the time that he was teaching me to see.

Can you think of the first time you realized the camera you owned was holding you back?

I have felt that so many times in my career! I always wanted to print bigger, have more resolution and detail, as I saw in hyper realism. I went through a slew of cameras before settling on my current setup with the IQ4-150. I still want more however as I continue to evolve and grow.

Describe your experience with DT and why you chose to shoot with Phase One gear.

DT has a support crew that helps me when I push the envelope. I’ve driven Joe King crazy but he keeps finding solutions, as well as the other pros. I started out with Leaf backs and graduated up to Phase One as everything in my business model has a “weakest link in the chain” potential point of failure. I market my portraits up to 120” tall and if someone like Shaquille O’Neal calls my bluff and wants a huge portrait, I need to be able to perform as a standard part of my offering. This way I can focus on composition and emotion and not have to worry about a final size. Any portrait I make can be made at any size a client wants.

How did you make the transition to professional photography, and how did making a living from photography impact your style of shooting?

I had a custom bicycle business that tanked in the 2008 recession, but it had a photo studio in there because it was a support system for the internet. I learned how to shoot on a 4 x 5, had a drum scanner, and pushed the envelope way back then. When I transitioned the studio to full time in 2012 I bounced from imploding market to imploding markets like so many pros and finally have found my calling in high end portraiture.

What was your most difficult project?

All my black and white high end sessions are difficult. I size up a client, talk to them for 45 minutes or so, laser beam them and get their angles and find out where they are coming from as a subject, then I place them in a circle of 8 lights. I then design the lighting scheme in real time based on what I think they can handle artistically and what I see, and then I get the shot in four exposures or less. Half the time I do it in one shot. It is high stress and very intense. It’s 98% psychology and 2% opening the shutter at the right time. There are many points of failure and no room for error. I have to get the minimum amount of information into the sensor so I can do my artistry on my time, not the clients, and I have to deliver every time. I can say the most difficult sessions and there are some, are when the subject won’t cooperate and doesn’t want to be there. I capture emotion at very high resolution, of course, so disconnects are so much more painful.

Another very challenging project was my fine art orchid project, which was about 100 final images. Each was either stitched for the large plants or focus stacked for the blooms and close ups. I used up to 100 images for each of the orchids and the hand work to get them perfect was very tedious.

If you had to do a project using the bare minimum of equipment, what would you bring?

I always use the bare minimum equipment. As Einstein said, one needs to be as simple as possible, but not simpler. I have used one light and available light. It all depends. At the end of the day, however, the bare minimum would be a camera, subject, and a suitable light source.

What’s the most interesting/surprising/invaluable thing you keep in your equipment bag?

I don’t go outside the studio these days so my equipment bag is empty. I run checklists daily before sessions so it’s boring, like an airline pilot, but necessary. I suppose the most important and interesting thing in my studio is the tether computer. I use Capture One of course and I will never chimp again. The confidence a client has in seeing the direction of the session in real time and the kinesthetic sense that is gained from knowing what a pose feels like and really seeing what it looks like is invaluable.

What is one thing you wish you knew when starting out?

I wish I knew how to price for profitability and market in a way that people understood value. It takes a long time to figure this out. I also stumbled along without a “voice” so my work was inconsistent until it wasn’t.

Do you have a “passion project” that you enjoy working on in your free time?

I have built a popup version of my studio to allow me to create portraits that are indistinguishable from those made in my main studio but do it all over the world. It was an idea spawned during Covid when the studio was shut down. I had banked on San Antonio being a destination city and now I had to pivot and create the ability to go to discerning clients anywhere in the world. It has completely changed my studio focus for the better. Now I have 25 travel cases plus three 30 x 40 framed prints with easels and can create portraits anywhere in the world that are indistinguishable from those created in the studio. It is a total game changer at the super high end, as those clients’ time is worth more than the cost of the private jet and the rental of a location space.

What’s your favorite activity or hobby outside of photography that you’ve experienced recently?

I was a trombonist and played in the Arkansas Symphony as well as soloed in front of many ensembles over the years. My current focus is strictly on the studio to gain international exposure.

Want to see more of Kevin Saunders’s work?

You can see more of Kevin’s work on his website, Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter.

All images featured in this article are courtesy of Kevin Saunders.